The following work has been done during my time at the CNRS-AIST JRL (Joint Robotics Laboratory), IRL, Japan for my undergraduate thesis under the supervision of Dr. Mitsuharu Morisawa with support from Rohan Singh.

Note: Detailed results and video clips can be found in the Results section below.

Objective

The primary objective of this work was to create a deep reinforcement learning based policy for quadruped locomotion with emphasis on minimal hand tuning for deployment and easy sim-to-real transfer which was to be used as a baseline policy in our future work.

This has been accomplished using an energy minimization approach for the reward function along with other training specifics like curriculum learning.

Hardware & Software

With the core belief of working towards a controller that can be deployed in real-world settings, it is extremely crucial that the entire framework of both software and hardware be scale-able and economically viable. We therefore went ahead with a commercially available quadruped platform rather than creating our own quadrupedal platform that might make the results more difficult to verify and the solution equally harder to be deployed in a commercial scale. Similar decisions have been taken wherever crucial decisions had to be taken.

AlienGo

The AlienGo quadrupedal platform (can be seen in the figure below) by Unitree Robotics first launched in 2018 was our choice for this research study as it strikes the perfect balance between economical cost, features and capabilities. Further, quadruped robots from Unitree Robotics have been one of the most common choice among research labs across the globe. Some select parameters of the robot are listed below:

- Body size: 650x310x500mm (when standing)

- Body weight: 23kg

- Driving method: Servo Motor

- Degree of Freedom: 12

- Structure/placement design: Unique design (patented)

- Body IMU: 1 unit

- Foot force sensor: 4 units (1 per foot)

- Depth sensor: 2 units

- Self-position estimation camera: 1 unit

MuJoCo

MuJoCo has been our choice for simulation as it is a free and open source physics engine that is widely used in the industry for research and development in robotics, biomechanics, graphics and animation. Also, we have observed that it is able to simulate contact dynamics more accurately and was also faster in most of our use cases when compared to other available options. We have also used Ray an open-source compute framework for parallelization of our training.

Training Platform

Our primary training platform is the GDEP Deep Learning BOX some select system parameters are mentioned below:

- CPU: AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 5975WX

- Num. Cores: 32

- RAM: 128GB

- GPU: Nvidia RTX A6000 x 2

RL Framework

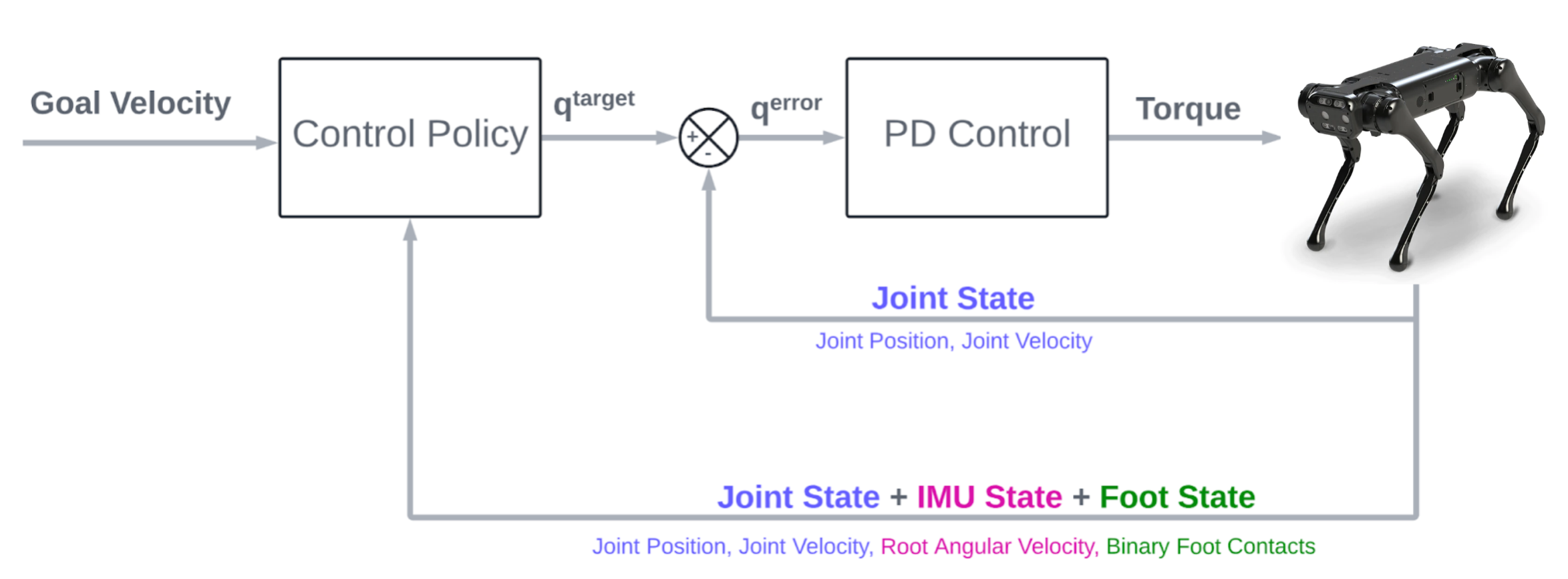

State Space

As stated in Jie Tan et al. Sim-to-Real: Learning Agile Locomotion For Quadruped Robots the choice of state space has a direct impact on the sim to real transfer, we note that this can be primarily summarized as the fewer dimensions in the state space the easier it is to do a sim to real transfer as the noise and drift increase with an increase in the number of parameters being included in the state space. Many of the recent papers on quadruped locomotion therefore try to avoid using parameters that are noisy or tend to drift such as yaw from the IMU and force values from the foot sensors. While a few papers use methods like supervised learning and estimation techniques to counter the noise and drift in sensor data we decided to eliminate the use of such parameters all together as it didn’t result in any drastic change in the performance of learning policy. Our final state space has 230(46x5) dimensions and its breakdown is listed below:

- $[\omega_x,\omega_y,\omega_z]$ - root angular velocity in the local frame

- $[\theta]$ - joint angles

- $[\dot{\theta}]$ - joint velocities

- $[c]$ - binary foot contacts

- $[v_x^g,v_y^g,\omega_z^g]$ - goal velocity

- $[a_{t-1}]$ - previous actions

- $[s_0,s_1,s_2,s_3]$ - history of the previous four states

The goal velocity consists of three components linear velocity in x and y axis along with angular velocity along the z axis, we have discarded the roll, pitch, yaw and linear velocities that are usually included in the state space for reasons mentioned above. Further, although aliengo has force sensors that can give the magnitude of the force we decided to use a threshold and use binary representation for foot contacts as there is significant noise and drift in the readings.

Action Space

As stated in Michiel van de Panne et al. “Learning locomotion skills using DeepRL: does the choice of action space matter? ”, the choice of action space directly effects the learning speed and hence we went ahead with joint angles as the action space representation, further to strongly center all our gait from the neutral standing pose of the robot. The policy outputs are added around the joint position values of the neutral standing pose joint angles before being fed into a low-gain PD controller that outputs the final joint torque values. The final control scheme can be seen here

Learning Algorithm

Given the continuous nature of the state and action space Approx methods are essential. We went ahead with Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm that is based on the Actor-Critic Framework as it do not require extensive hyperparamter tuning and are in general is quite stable. We use a Multi Layered Perceptron architecture with 2 hidden layers of size 256 units each and ReLU activation to represent both the actor and critic networks.

Hyperparameters

The hyperparameters were taken from standard implementations which are typically the same across many of the papers. The values have been listed below:

- Parallel Instances: 32

- Minibatch size: 512

- Evaluation freq: 25

- Adam learning rate: 1e-4

- Adam epsilon: 1e-5

- Generalized advantage estimate discount: 0.95

- Gamma: 0.99

- Anneal rate for standard deviation: 1.0

- Clipping parameter for PPO surrogate loss: 0.2

- Epochs: 3

- Max episode horizon: 400

Reward Function

The goal for any reinforcement learning policy is to maximize the total reward/expected reward collected. While the state and action space definitely effect the learning rate and stability of the policy, the reward function defines the very nature of the learning policy. The wide variety of literature available on locomotion policies for quadrupeds while almost the same with respect to the state and action space has diversity mostly due to the choice of the reward function.

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Total Reward} &= \text{Energy Cost} + \text{Survival Reward} + \text{Goal Velocity Cost} \\ \text{Energy Cost} &= C_1\tau\omega \\ \text{Survival Reward} &= C_2|v_x^g| + C_3|v_y^g| + C_4|\omega_z^g| \\ \text{Goal Velocity Cost} &= -C_2|v_x-v_x^g| - C_3|v_y-v_y^g| - C_4|\omega_z - \omega_z^g| \\ \end{aligned}\]Where $C_1,C_2,C_3,C_4$ are constants that have to be picked.

We believe that the primary reason reinforcement learning based policies generalize poorly is due to the excessive number of artificial costs added to the reward function for achieving locomotion. Inspired by Zipeng Fu et al. Minimizing Energy Consumption Leads to the Emergence of Gaits in Legged Robots, we base our reward function on the principle of energy minimization. Another added benefit of energy minimization based policy is the fact that different goal velocity commands result in different gaits. As explained in Christopher L. Vaughan et al. “Froude and the contribution of naval architecture to our understanding of bipedal locomotion.”, this is consistent with how animals behave and is because a particular gait is only energy efficient for a particular range of goal velocities.

Curriculum Learning

Curriculum learning is a method of training reinforcement learning (RL) agents in which the difficulty of tasks or environments is gradually increased over time. This approach is based on the idea that starting with simpler tasks and gradually increasing the complexity can help the agent learn more efficiently. The agent can focus on mastering basic skills needed to solve the initial tasks before attempting to tackle more complex ones. There are two ways in which curriculum learning is usually implemented. One is to use a pre-defined set of tasks or environments that are ordered by increasing difficulty. The agent is trained on these tasks in a specific order, with the difficulty of the tasks increasing as the agent progresses through the curriculum. Another approach is to use a dynamic curriculum, where the difficulty of the tasks is adjusted based on the agent’s performance. For instance, if the agent struggles with a particular task, the difficulty of that task may be reduced, while the difficulty of easier tasks may be increased to provide more challenge. We use Curriculum learning in a variety of ways to tackle a varity of issues as discussed below.

Cost Curriculum

The high energy cost with low reward for smaller values of goal velocity make it extremely difficult for the agent to learn walking at low goal speeds as it settles in a very attractive local minima of standing still and not moving at all to reduce the cost associated with energy rather than to learn how to walk. Using a Cost Curriculum, we first let the agent walk at the required low speed with almost zero energy cost and once the agent learns a reasonable gait we slowly increase the cost to its original value so that the gait is fine tuned to be energy efficient.

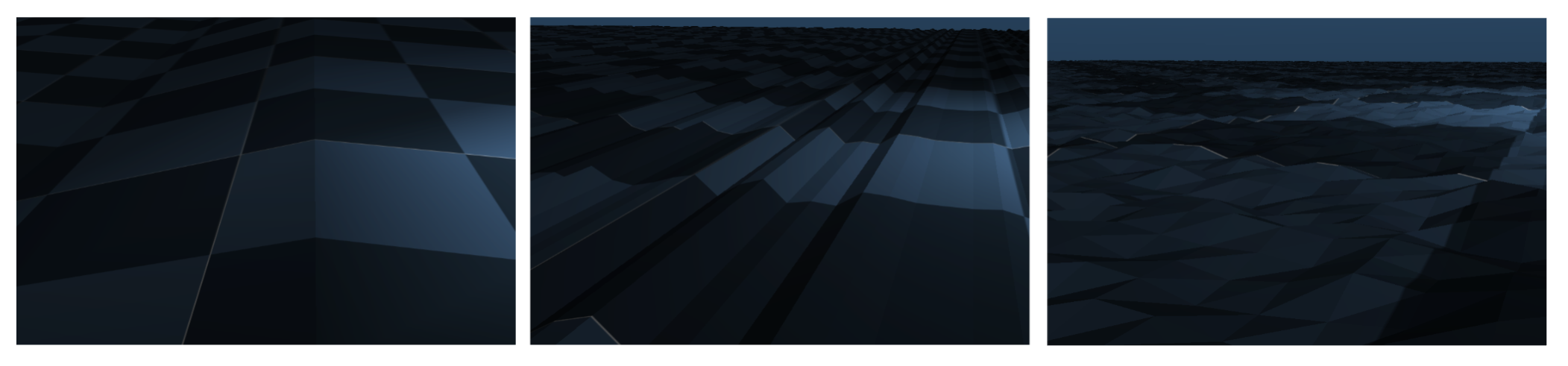

Terrain Curriculum

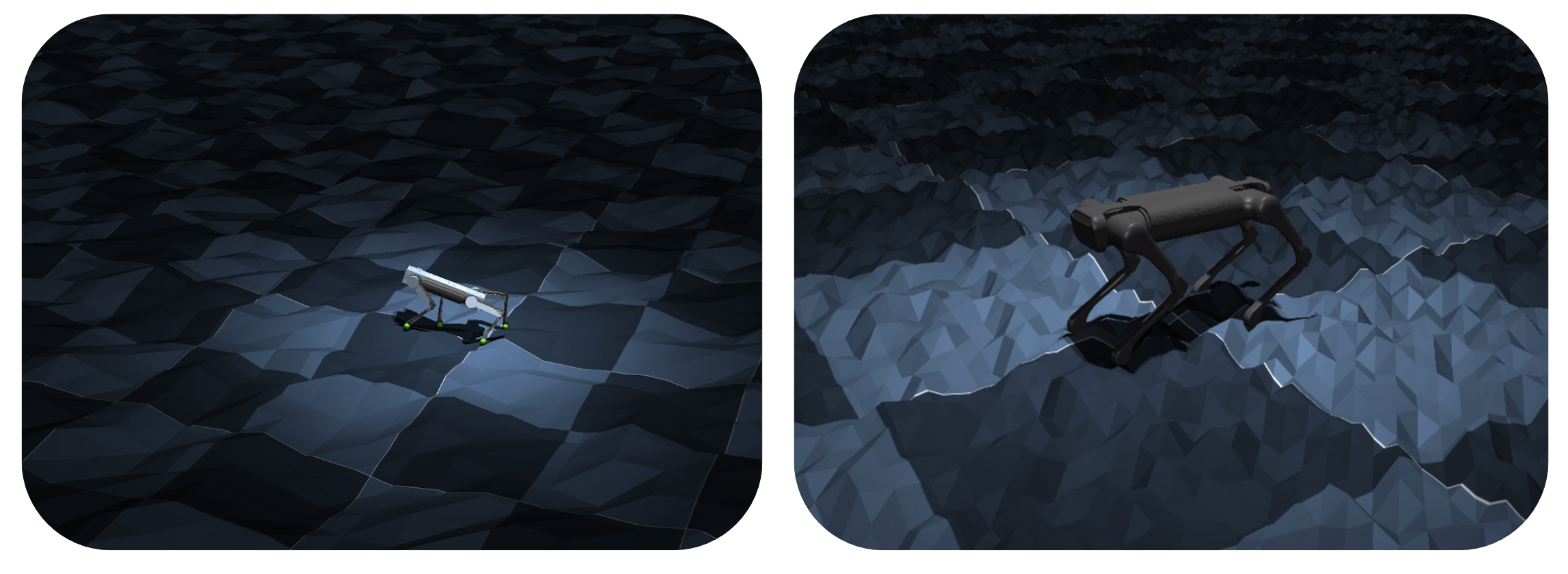

For increasing robustness against external perturbation and for better adaptability to real world use cases where the ground is not plane and uniform, it is useful to train the agent in uneven terrain during simulation. But introducing difficult terrain from the beginning of the training might hinder the learning and in some cases the agent might never completely solve the task as the difficulty is too high. Using terrain curriculum enables us to start with a flat plain initially

and gradually increase the difficult of the terrain to make sure the learning rate is not too difficult that the agent makes no progress at all. We train the agent across two different terrains (Plain

and Triangle) and test the learnt policy in 2 additional environments (slope and rough).

Velocity Curriculum

Training the agent for a single goal velocity while might result in faster training speed, having the ability to smoothly transition between various goal speeds is often crucial and this is especially important when we want the policy to adapt to any combination of linear and angular velocity given during evaluation by the user. Therefore, using a velocity curriculum enables us to randomize and cover the whole input velocity domain systematically.

Terminal Conditions

Termination conditions enable faster learning as they help the agent only explore states which are useful to the task by stopping the episode as soon as the agent reaches a state from which it cannot recover and any experience gained by the agent from that state onwards does not help the agent learn or get better at solving the task at hand. We use two termination conditions to help increase the training speed, both of which are discussed below

Minimum Trunk Height

This condition ensures that the Center of Mass of the trunk is above 30cm from the ground plane as any kind of walking gait should ensure that the trunk height isn’t too low from the ground. This enable the agent to learn how to stand from a very early stage in the training speeding up the overall learning.

Bad Contacts

This condition ensures that the only points of contact the agent has with the ground plane are through the feet and no other parts of the agent are in contact with the ground plane. This minimizes the probability of the agent learning gaits or behaviours which result in collision between the agents body and the ground plane minimizing damage to agent body and other mechanical parts during deployment.

Sim to Real

Sim-to-real transfer refers to the problem of transferring a reinforcement learning agent that has been trained in a simulated environment to a real-world environment. This is a challenging problem because the simulated environment is typically different from the real-world environment in many ways, such as the dynamics of the system, the sensors and actuators, and the noise and uncertainty present in the system.

We employ a mix of domain randomization and system identification for sim-to-real transfer.

Results

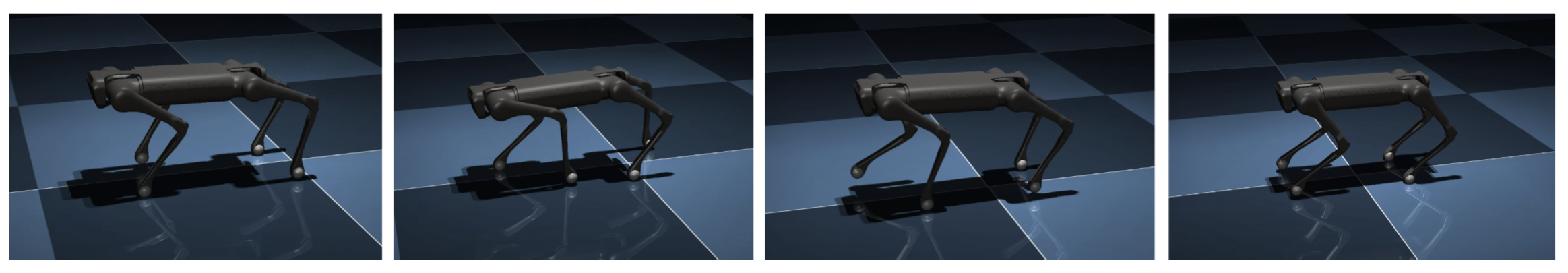

The energy minimization based policy is able to adjust its gait to the most optimal gait based on the given goal velocity. Traditional policies that do not use energy minimization are only able to exhibit a single gait.

All the below videos/picture frames are from a single policy with no changes made other than the goal speed.

Gaits

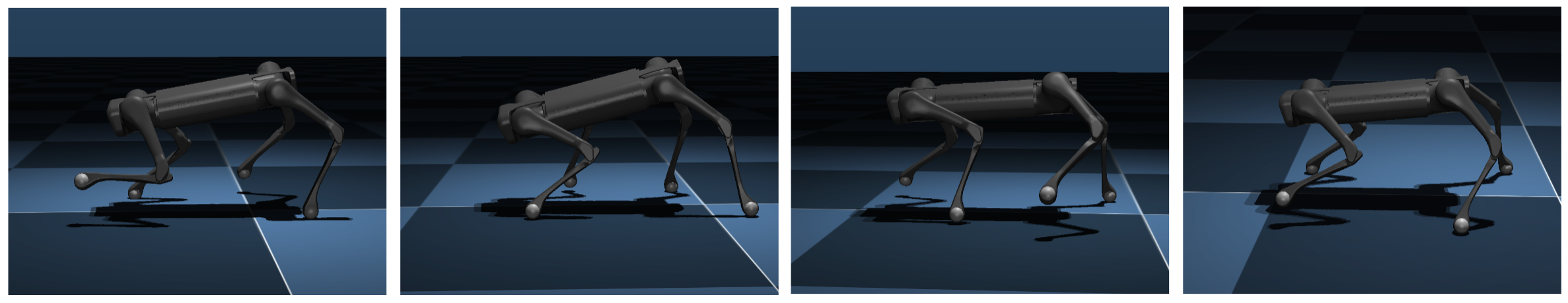

Walk

Generating walking gait at low-speed required the use of curriculum learning as the agent found an attractive local minima where It would just stand still without moving to avoid energy costs at low speeds. Furthermore, curriculum learning was used as the primary sim to real transfer technique along with domain randomization.

Terrain curriculum in particular resulted in better foot-clearance and made the agent robust to external perturbations enabling the robot to walk on extremely difficult terrain.

Terrain curriculum in particular resulted in better foot-clearance and made the agent robust to external perturbations enabling the robot to walk on extremely difficult terrain.

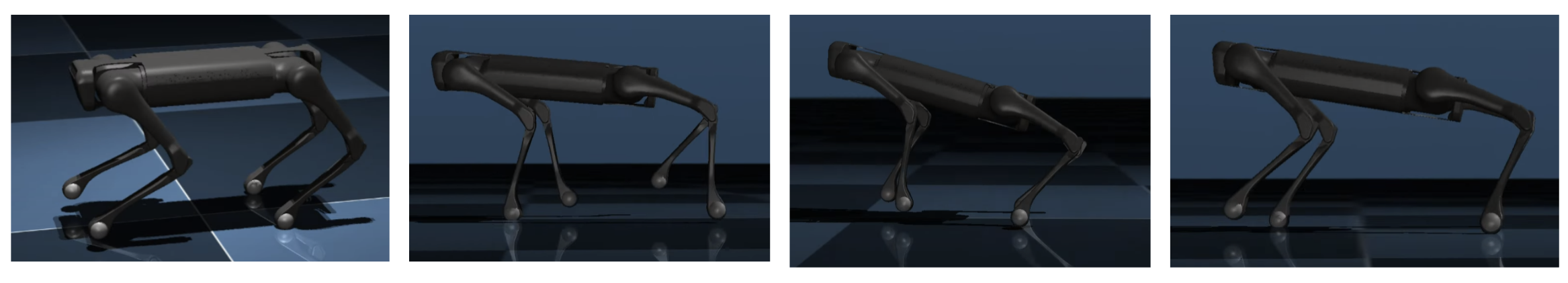

Trot

This is one of the most commonly generated gait for use in legged locomotion, while other methods are able to generate trotting gait we believe that our method enables us to use less

energy and torque to reach the same target velocities.

Gallop

While we see a Galloping gait emerge at goal speeds greater than 1.65 m/s in simulation, we need to test if the robot hardware can physically achieve this speed and therefore exhibit the

gallop gait. The other possible alternative is to use a much lower energy cost to make the agent

exhibit the gallop gait at a lower goal velocity.

Directional Control

Using velocity curriculum described above, the agent is trained using a random goal velocity vector that consists of linear and angular velocity components. This enables the agent

to learn not only how to walk but also how to bank and turn in the process.

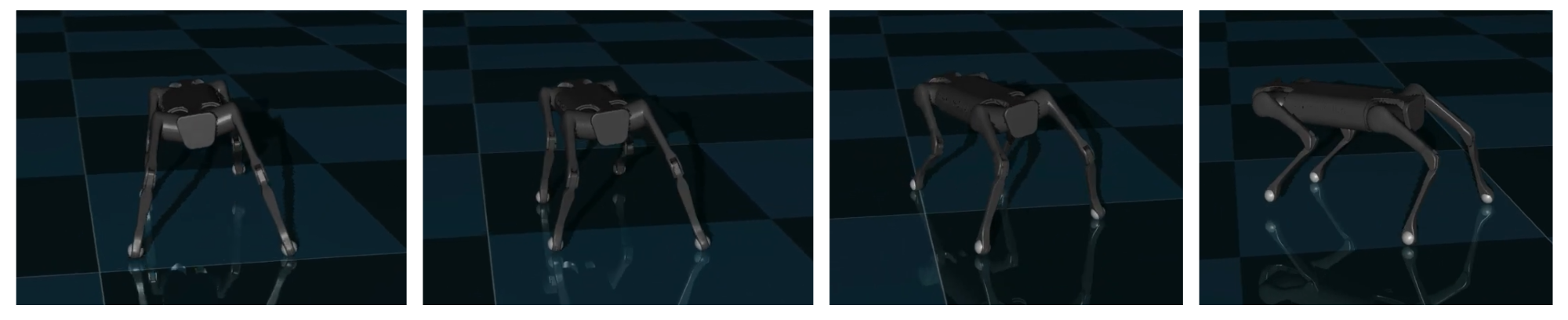

Emergence of Asymmetrical Gait

Training in extremely uneven terrain leads to the emergence of asymmetrical gait that maintains

a low center of gravity and shows almost a crab like walking behaviour which is persistent even

when the policy is deployed on a smoother terrain. The results of the training are labelled as

CP2 and have been described in the latter sections.

Adaptation to Unseen Terrain

While the agent has been trained in the triangle terrain, the learnt policy is able to successfully

walk on new terrain that it has not seen during training. The base-policy is referred to as BP,

the base policy is then subjected to two different curriculum resulting in policies CP1 and CP2.

While both CP1 and CP2 are trained in the Triangle Terrain 1 & 2 the maximum height of the triangular peaks for CP2 is 0.12m (Triangle Terrain 2) while it is 0.10m for CP1

(Triangle Terrain 1).

All the three curriculum’s have been tested on unseen terrains rough with maximum peak height of 0.12m and slopes with max slope height of 0.8m and slope of 32 degrees. The results are as

follows:

Inference

While CP2 has a clear advantage when deployed in Triangle Terrain 2, it performs almost as good as or slightly worse than CP1 in all the other test cases. Furthermore, it is clearly visible that BP isn’t suitable for most of the testing environment as it flat-lines pretty early. While CP2 learns a more stable gait pattern it is slower and requires lot more movement by the agent which results in CP1 gaining a few points over it as CP1 can quickly cover the velocity cost.

Conclusion

Most of the current reinforcement learning based policies use highly constrained rewards due to which the locomotion policy developed doesn’t use the entire solution space. Energy minimization based policy is able to adjust its gait to the most optimal gait based on the goal velocity. Traditional policies that do not use energy minimization are only able to exhibit a single gait.

Current Limitations

The current implementation of the policy although exhibits different gaits when trained at different goal velocities, it fails to learn more than one gait during a single training run. We believe this is due to the difference in the weights of the network for different gaits. Also, while training in extremely unstructured environments leads to the emergence of asymmetrical gait that is extremely stable, the policy seems to forget the older gait and tends to use this gait even when deployed later on plain terrain